Guldagergaard week 4

The past week has been an odd mix of very busy and very relaxed. We finished the soda firing last Friday, and I spent the weekend relaxing and starting some preliminary work on the installation frame. However, as soon as Monday came, life kicked up into full speed once again.

Mette, the wonderful director here at GG, has arranged it so I could install “Swarm” temporarily in a local elementary school. We met with a school official Monday morning, who asked when I could start installing it. Despite the fact that the pieces were all still in the kiln at the time and the framework was barely started, I decided to be optimistic and said I could start on Wednesday. This was setting myself up for a lot of work in a short period of time, but then again, that’s what I’m here in Denmark to do!

As soon as I got back from the school, it was time to get the kiln unloaded and get myself to work. While I was fairly happy with how my work came out, but it turned out the soda firing held some surprises. The main one was the way that Jody’s work reacted to the firing. Her work is made of thrown porcelain which has been cut apart, manipulated, and reassembled. While it’s visually all about movement, we weren’t expecting the fact that the pieces themselves moved a huge amount during the firing! Every nearly single piece warped, fell or tilted. The mystery of the overly long and difficult firing was solved when we discovered that two to three pieces of hers had fallen into the firebox, blocking off most of the path of the flame into the kiln. In the end though, she seemed ok with some of her results, and started to get excited about some of the new creations that formed as a result of the firing.

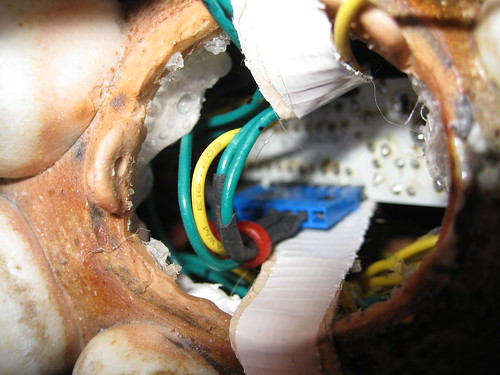

On my part, I didn’t loose a single piece, which is a very luck situation. Overall, while I’m still not sure soda firing is really for me I’m still quite happy with the results of this firing. It seemed to have work especially well with Swarm. Anyway, as soon as my pieces were out of the kiln, I got to work on the installation framework. It was my plan to make a wooden frame containing a metal grid. Each flier would be hung from parallel strands of fishing line, which would run up to a stick that’s a bit longer that the mesh work of the grid. That way, hanging each flier from the grid would be as simple as slotting the stick through the grid and letting it catch, like a button on a coat. While this worked as well as I hoped it would, the frame and hangers took no less that five trips to the hardware store along with many many hours of very hard work. I also totally owe my friend Rachel Van Wagoner who spent several hours helping me string fliers on fishing line.

However, in the end, everything came together for Swarm. I’m extremely happy with how it’s worked out. It’s taken weeks of hard work and hours spent walking up and down a ladder, but I think it’s all worth it. This idea of thing hanging together in space is one that I keep coming back to, much like my city beasts. In fact, my parents recently reminded me of a ninth or tenth grade math project, where I tried to build a three dimensional diagram of the golden spiral using ping pong balls and fishing line inside a plexiglas cube. The end result was giant, clunky, and awful looking, but evidently planted some thoughts about space and sculpture that have stayed with me to this day. It’s wonderful to finally have created something that properly explores those ideas. Here’s a brief video tour I made of it. The video accidentally got shortened by flickr, but I’ll be making a longer one with proper lighting soon.

Tomorrow I’ll be heading back to the school for an opening reception, complete with snacks, tours by some of the older students, and music sung by the students in the grand tradition of Danish fantasy ballads! It also apparently will include a speech, by me, to the students. I better go figure out what I’m going to say and see if I can finally manage to pronounce Guldagergaard in such a way that it doesn’t cause all Danes in the vicinity to burst into laughter.